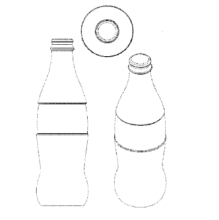

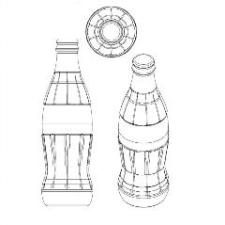

On 29 December 2011 The Coca-Cola Company filed an application at OHIM for registration of a Community trademark of the following three-dimensional sign consisting of the shape of a bottle (on the left), a variation of the popular Coca-Cola contour bottle with fluting (on the right):

On January 2013 the examiner dismissed the application having found that the mark applied for was devoid of distinctive character (under Article 7 (a)(b) of regulation No 207/2009) and had not acquired said character through use (under Article 7(3)). The applicant filed a notice of appeal with OHIM against the examiner’s decision, which was however dismissed by the OHIM Board of Appeal.

Against the decision of the Board of Appeal The Coca-Cola Company brought action before the EU General Court, which on 24 February 2016 (in case T-411/14, full text here) entirely dismissed the appeal and, as a consequence, confirmed the previous ruling of OHIM Board Appeal.

With two pleas Coca-Cola claimed: (a) that the mark it applied for has a distinctive character, being a natural evolution of the shape of the bottle “contour” with fluting which is popular and distinctive worldwide; and (b) that in any event mark it applied for has acquired distinctive character throughout the use in the market in combination with the contour bottle with fluting.

Taking into account the first plea, the General Court recalled that the distinctive character must be assessed by reference to (i) the goods or services in respect of which registration has been applied for, and (ii) the perception of them by the relevant public.

More specifically, it emphasized, when those criteria are applied account must be taken of the perception of the average consumer in relation to a three-dimensional mark consisting of the appearance of the goods themselves: in this respect average consumers are not in the habit of making assumptions about the origin of goods on the basis of their shape or the shape of their packaging in the absence of any word or graphic element, and it could therefore prove more difficult to establish distinctive character in relation to such a three-dimensional mark than in relation to a word or figurative mark.

Then, the Court examined the mark applied for, founding that either the lower, the middle and the top section of the bottle (i) do not enable the average consumer to infer the commercial origin of the goods concerned and (ii) do not display any particular features which stand out from what is available on the market.

Therefore, considering the mark applied for as a whole, the Court held that it is devoid of distinctive character for being a mere variant of the shape and packaging of the goods concerned, which will not enable the average consumer to distinguish the goods of Coca-Cola from those of other undertakings.

In considering the second plea, the Court underlined that for the mark to have acquired distinctiveness through use, Coca-Cola has the burden to demonstrate that at least a significant proportion of the relevant public throughout the European Union, by virtue of that mark, identifies the goods or services concerned as originating from Coca-Cola.

In evaluating that, the Court examined all the items of evidence already provided by Coca-Cola to the OHIM Board of Appeal, founding that none of them, considered both in isolation and as a whole, was sufficient to establish that the mark applied for has acquired distinctive through use.

In particular, the surveys submitted by the applicant covered only a part of the European Union (only 10 of 27 Member States) and the other secondary evidences such as investments, sales figures, advertising and articles did not, due to their imprecisions and inconsistencies, compensate for that deficiency: For example, the sales figures proved that Coca-Cola has sold large beverages throughout the EU, but the data provided referred to the ‘contour bottle’ without specifying whether that means the mark applied for or the contour bottle with fluting, consequently it does not enable a conclusion to be drawn regarding the relevant public’s perception of the three-dimensional sign applied for.

Furthermore, the Court pointed out that in general a three dimensional mark may acquire distinctive character through use, even if it is used in conjunction with a word mark or a figurative mark, when the relevant class of persons actually perceive the goods or services, designated exclusively by the mark applied for, as originating from a given undertaking (as stated in case C-353/03, Nestlè SA v. Mars UK Ltd). However, in the case in point the Court noted that the mark which Coca-Cola applied for was not clearly distinguishable from the mark it was alleged to be a part of, due to the fact that it was not obvious from the evidence provided by the applicant and particularly from the advertising material, whether the bottle that is shown in them is a representation of the contour bottle with fluting, or a representation of the mark applied for.

In view of the above, the General Court found that the mark Coca-Cola applied for has not even acquired distinctive character.

We can only agree with the whole outcome: to grant a trade mark in these circumstances would have given a perpetual monopoly to Coca-Cola in the shape of a bottle that is very commonplace on the market. The General Court set forth its arguments in a commendable way without being affected by the global popularity of Coca-Cola and its famous iconic bottle contour with fluting.

It remains to be seen whether, within two months of notification of the decision, Coca-Cola appeal the decision of the General Court to the Court of Justice of the European Union.

It may be not a coincidence and neither a déjà vu, but in the 1986 the House of Lord (Coca-Cola Co.’s Application [1986] 2 All ER 274) denied the Coca-Cola Company trademark protection for shape and design of the Coke bottle, assuming that it was “another attempt to expand on the boundaries of intellectual property and to convert a protective law into a source of monopoly”.

Matteo Aiosa

General Court of EU (Eight Chamber), The Coca-Cola Company v. Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market, 24 February 2016, case T-411/14