On March 14, 2019, the CJEU ruled on two preliminary questions submitted by the Court of Appeal of Stockholm in the case Textilis – Keskin v Svenskt Tenn (C-21/18).

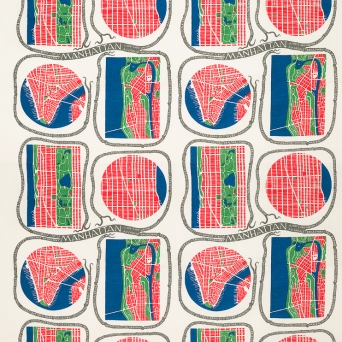

Svenskt Tenn, as trademark and copyright holder over a renowned design pattern of a furnishing fabric, filed a lawsuit against Textilis, a UK company that sells textiles in the UK, arguing infringement of its rights and asking for an injunction prohibiting such sales.

Svenskt Tenn, as trademark and copyright holder over a renowned design pattern of a furnishing fabric, filed a lawsuit against Textilis, a UK company that sells textiles in the UK, arguing infringement of its rights and asking for an injunction prohibiting such sales.

Textilis in turn filed a counterclaim arguing for the invalidation of the EUTM on the grounds of lack of distinctiveness (Article 7(1)(b) EUTMR) and since it would consisted of a shape which gives substantial value to the goods (Article 7(1)(e)(iii) EUTMR).

On March 22, 2016 the Stockholm District Court found that Textilis was guilty of trade mark and copyright infringement. The court noted that Textilis had not provided any evidence that the trade mark in question lacked distinctiveness. In relation to Article 7(1)(e)(iii), the court dismissed the claim simply based on the fact that the contested trade mark does not consist of “a shape” within the meaning of Article 7(1)(e)(iii) of EUTMR.

Textilis then appealed that decision before the Court of Appeal, Patents and Market division, in Stockholm.

The Swedish Court of Appeal focused on the interpretation of Article 7(1)(e)(iii) of Reg. 207/2009. In particular, the CJEU was asked to rule on the meaning of the wording “consist exclusively of the shape” (used both in the original text of the EUTMR provision and in the new Regulation No 2015/2424 (“EUTMR as amended”) which entered into force on March 23, 2016) and whether its scope encompasses a sign consisting of the two-dimensional representation of a two-dimensional product, such as the fabric decorated with the sign in question.

The CJEU observed that, since the EUTMR does not provide any definition of the term “shape”, its meaning must be established with reference to its usual meaning in everyday language, while also considering the context in which it occurs and the purposes of the rules to which it belongs.

The CJEU affirmed that “it cannot be held that a sign consisting of two-dimensional decorative motifs is indissociable from the shape of the goods where that sign is affixed to goods, such as fabric or paper, the form of which differs from those decorative motifs”.

The CJEU recalled its previous Louboutin decision (Case C‑163/16), where it established that the application of a particular color to a specific location of a product does not mean that the sign in question consists of a “shape” within the meaning of Article 3(1)(e)(iii) of Directive 2008/95. This is because what the applicants intended to protect through the trademark registration in Louboutin was not the form of the product or part of the product on which it may be affixed, but only the positioning of that color in that exact location.

The Court also added that the fact that the drawings covered by the Trademark enjoy copyright protection does not affect this finding in any way.

Therefore, the CJEU concluded that the exclusion from registration established in Article 7(1)(e)(iii) of EUTMR is not applicable to the sign at issue in the main proceedings on the grounds that “a sign such as that at issue in the main proceedings, consisting of two-dimensional decorative motifs, which are affixed to goods, such as fabric or paper, does not ‘consist exclusively of the shape’, within the meaning of that provision”.

Judgment of the Court (Fifth Chamber) of 14 March 2019, Textilis Ltd and Ozgur Keskin v Svenskt Tenn Aktiebolag, Case C-21/18

Jacopo Ciani