In recent years, trademark offices worldwide have been assisting to a new trend: brand owners are increasingly trying to protect hashtags as trademarks. However, some substantive differences existing between these two figures suggest that trademark protection is most of the time improper – and even unnecessary. This, for a number of reasons.

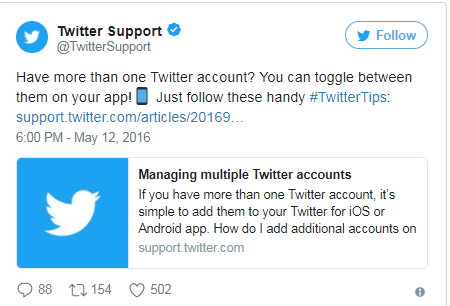

- A hashtag can be defined as the symbol # followed by a word, a phrase or a symbol. Hashtags are used on social media in connection to a certain content to synthetically describe or comment it. They were firstly introduced on Twitter, then the main other social networks followed. It must be emphasized, even for legal purposes, that they are freely usable by anyone.

Technically, the social network indexes and groups all the contents using the same hashtag. Hashtags function as hyperlinks: by clicking on a single hashtag, the user is redirected to a page where all the contents using the same hashtag have been grouped and organized together by the social network.

From a consumers’ view, hashtags are helpful in following topics and finding contents. From a brand’s view, they are useful to control and attract online consumer traffic and enhance the brand appeal. In particular, hashtags are used in advertising campaigns to redirect users to the company website and social networks, where the consumer experience can be enhanced and the brand loyalty reinforced. From a social network’s view, they are a new way of organizing information and topics.

- Let’s come to trademarks. As known, besides their essential legal function of indicating the origin of the product or service covered by the trademark, they can perform, if famous (“with reputation”) other factual functions, such as that of ‘guaranteeing’ the quality of a product or service, or that of supporting advertising of, and investment on, the ‘brand’. However, it must be noted that quite often hashtags are not perceived as trademarks, as they do not perform any of the above functions.

Focusing on the distinctive function, if a sign does not have distinctive character the trademark owner shall retain its exclusive right only by proving that the sign has acquired – typically by strong advertising – a ‘secondary meaning’ – i.e.- the capacity to identify, in the eyes of consumers, the product or service as originating from a firm.

Now, as concerns hashtags, it seems all too evident that, except when the word component is wholly or in part of coincident with a trademark already known on the market (e.g. #cokecanpicks or #CokeZeroSugar, as in the below example), it is indeed hard to say that a hashtag is inherently distinctive: in such cases, it would be normally necessary to prove secondary meaning to secure a valid registration.

In this respect, hashtags shall be considered as a mix of domain names and slogans. As for the top level domain names such as “.com” or “.it”, the symbol “#” is considered as not capable of conferring to the sing any distinctive value. Therefore, if the word or the phrase composing a hashtag are not per se distinctive, the presence of the symbol # cannot save the trademark from being prevented registration for lacking of distinctive character. On the other hand, hashtags are often composed by small phrases and shall, therefore, be compared to slogans. As for slogans, the proof of the existence of a distinctive character is more difficult than for ordinary trademarks, as slogans are usually not perceived as source indicators. Against this background, it seems more efficient to try to secure registration to a phrase or word, and not to the same in the form of a hashtag.

Further, their functional character may prevent hashtags registration as trademarks. The functionality doctrine, based on the ‘imperative of availability’ (“the need to keep free”, “Freihaltebeduerfnis”) prevents to use trademark law for inhibiting legitimate competition by allowing a single company to claim a monopoly either on a descriptive term or a useful product feature. And a product feature is considered functional if it is essential to the use or purpose of a good. Now, as hinted, hashtags function as hyperlinks and tags, to group contents. This function is essential for their success.

In the light of the considerations just submitted registering a hashtag as trademark could be quite difficult. That said, provided that a company succeeds in obtaining trademark registration, its enforcement towards third parties could be difficult for a number of reasons:

a) in most cases, hashtags are not perceived as trademarks. As said, they are typically a form of metadata or tag, through which a word or a phrase becomes a searchable expression on a social network. On the one hand, therefore, it is inevitably that the hashtag registered as trademark is used by all social network users willing to do so. Such users would likely not perceive the hashtag as a trademark, a source indicator, but more likely as a descriptive text or as a tool having a specific function.

Obviously, though, trademark owners have an interest to control the use of their hashtag, if registered as trademark, in order to protect it from dilution and/or consumer confusion with a similar trademark. Here lies one of the most strident paradoxes of hashtag registration as trademarks: as trademark registrants, hashtag owners are encouraged to enjoin unauthorized third parties from using their registered sign. At the same time, it is their interest to encourage social network users to make use of the hashtag for commercial benefits — expand brand awareness, ‘lock in’ consumers, and so on. More precisely, brand owners use hashtags in social media contexts for marketing purposes, often in a way that results detrimental to their distinctive character (and, as a consequence, to their possible enforcement). They convert the hashtag into a means through which the public is encouraged to comment, share and ‘talk’ about the brand and its products or service, while gathering information and data about consumers tastes, preferences and so on. Thus, again, notwithstanding a possible registration, even registered hashtags are hardly used as indicators of origin, but merely as collectors of data and comments (of course not possibly subject to any monopoly).

b) Even when hashtags are used and perceived as trademarks, descriptive use, functionality, legitimate use play in most cases play a crucial role in excluding the existence of a trademark infringement.

Here, the constitutionally ranking principle of freedom of expression would play a role in determining where there is a legitimate use of a hashtag. If people are encouraged to use a hashtag to get involved in a topic and participate to a discussion, their use of the hashtag, as such, shall be considered indeed legitimate under the principle of freedom of expression.

c) Therefore, the sole relevant case when the use of hashtags could be protected under trademark law seems that of competitors adopting hashtags confusingly similar to a hashtag that includes (or corresponds to) a registered trademark. This position seems reflected by the main social networks policies, preventing the use of third parties trademarks when such use creates confusions for consumers.

But even in such a case, there is room to affirm that the use of an identical or similar hashtag by a competitor is legitimate. Considering that the hashtag is a means to tag and categorize contents, the well-known case law on keyword advertising could well apply to a third party use of a registered hashtag. In this context, if the use a third party hashtag by a competitor enhances competition and offers consumes an alternative or a wider range of offer, this use could be considered fair according to the keyword advertising case law.

One last remark. Trademark law is just one of several laws that are relevant to the use of hashtags. Among others, privacy law, consumer law, licensing, image rights and advertising are strictly connected to hashtags use and shall be carefully considered by all users adopting hashtags.

Maria Luigia Franceschelli