The 1st of January of each calendar year marks not only the days full of new years’ hope, resolutions, and promises, but also the public domain day. 1 January 2021, a moment full of hope with the anti-COVID vaccine rolling out, is no different for copyright law purposes. On the 1st of January, many copyright protected works fell in the public domain.

This year marked the falling into the public domain of the works of George Orwell. Born in 1903, under the real name of Eric Arthur Blair, he has authored masterpieces such as ‘1984’ and ‘Animal Farm’, which in recent years have become extremely topical and relevant. In early 2017, the sales of ‘1984’ went so high up that the book became a bestseller once again. Some have suggested this is a direct response to the US Presidency at the time in the face of Donald Trump.

Orwell passed away in 1950, which means that, following the life of the author plus seventy years rule as per Article 1 of the Term Directive, copyright in Orwell’s works expired on 1 January 2021. Despite this, in the last several years an interesting trend has prominently emerged. Once copyright in famous works, such as those at issue, has expired, the body managing the IPRs of the author has often sought to extend the IP protection in the titles by resorting to trade mark applications. At the EUIPO, this has been successful for ‘Le journal d’Anne Frank’ (31/08/2015, R 2401/2014-4, Le journal d’Anne Frank), but not for ‘The Jungle Book’ (18/03/2015, R 118/2014-1, THE JUNGLE BOOK) nor ‘Pinocchio’ (25/02/2015, R 1856/2013-2, PINOCCHIO).

This is the path that the ‘GEORGE ORWELL’, ‘ANIMAL FARM’ and ‘1984’ signs are now following. The question of their registrability as trade marks is currently pending before the EUIPO’s Grand Board of Appeal. This post will only focus on the literary work titles – ‘ANIMAL FARM’ and ‘1984’, as the trade mark protection of famous authors’ personal names is a minefield of its own, deserving a separate post.

The first instance refusal

In March 2018, the Estate of the Late Sonia Brownell Orwell sought to register ‘ANIMAL FARM’ and ‘1984’ as EU trade marks for various goods and services among which books, publications, digital media, recordings, games, board games, toys, as well as entertainment, cultural activities and educations services. The Estate of the Late Sonia Brownell Orwell manages the IPRs of George Orwell and is named after his second and late wife – Sonia Mary Brownwell.

The first instance refused the registration of the signs as each of these was considered a “famous title of an artistic work” and consequently “perceived by the public as such title and not as a mark indicating the origin of the goods and services at hand”. The grounds were Article 7(1)(b) and 7(2) EUTMR – lack of distinctive character.

The Boards of Appeal

The Estate was not satisfied with this result and filed an appeal. Having dealt with some preliminary issues relating to the potential link of ‘ANIMAL FARM’ to board games simulating a farm life, the Board turned to the thorny issue of registering titles of literary works as trade marks. The Board points out that while this is not the very first case of its kind, the practice in the Office and the Board of Appeal has been diverging. Some applications consisting of titles of books or of a well-known character are registered as marks since they may, even if they are well-known, still be perceived by the public also as an indicator of source for printed matter or education services. This was the case with ‘Le journal d’Anne Frank’. Other times, a famous title has been seen as information of the content or the subject matter of the goods and services being considered as non-distinctive and descriptive in the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) and (c) EUTMR. This was the case for ‘THE JUNGLE BOOK’, ‘PINOCCHIO’ and ‘WINNETOU’. The EUIPO guidelines on this matter are not entirely clear. With that mind, on 20 June 2020, the case has been referred to the Grand Board of Appeal at the EUIPO. Pursuant to Article 37(1) of Delegated Regulation 2017/1430, the Board can refer a case to the Grand Board if it observes that the Boards of Appeal have issued diverging decisions on a point of law which is liable to affect the outcome of the case. This seems to be precisely the situation here. The Grand Board has not yet taken its decision.

Comment

The EUIPO’s Grand Board is a bit like the CJEU’s Grand Chamber – cases with particular importance where no harmonised practice exists are referred to it (Article 60, Rules of Procedure, CJEU). The Grand Board has one specific feature which the other five ‘traditional’ Boards lack. Interested parties can submit written observations, the otherwise known ‘amicus curiae’ briefs (Article 23, Rules of Procedure of the EUIPO Boards of Appeal). In fact, in this specific instance, INTA has already expressed its position in support of the registration of the titles.

It must be observed here that when the trade marks were filed, back in March 2018, ‘Animal farm’ and ‘1984’ were still within copyright protection (but not for long). Indeed, the Estate underlines in one of its statements from July 2019 that “George Orwell’s work 1984 is still subject to copyright protection. The EUIPO Work Manual (ie, the EUIPO guidelines) specifically states that where copyright is still running there is a presumption of good faith and the mark should be registered”. While this is perfectly true, what is also important to mention here is that trade mark registration does not take place overnight, especially when it comes to controversial issues such as the question of registering book titles as trade marks.

The topic of extending the IP life of works in which copyright has expired has seen several other examples and often brings to the edge of their seat prominent IP professors, as well as trade mark examiners and Board members. Furthermore, several years ago, the EFTA court considered the registrability as trade marks of many visual works and sculptures of the Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland (see the author’s photo below).

At stake here was a potential trade mark protection for an artistic work in which copyright had expired. One of these is the famous ‘Angry Boy’ sculpture shown here. The Municipality of the city of Oslo had sought trade mark registration of approximately 90 of Vigeland’s works. The applications were rejected. The grounds included not only the well-known descriptiveness and non-distinctiveness, but also an additional objection on the grounds of public policy and morality. Eventually, the case went all the way up to the EFTA court. The final decision concludes that “it may be contrary to public policy in certain circumstances, to proceed to register a trade mark in respect of a well-known copyright work of art, where the copyright protection in that work has expired or is about to expire. The status of that well known work of art including the cultural status in the perception of the general public for that work of art may be taken into account”. This approach does make good sense as it focuses on the specific peculiarities of copyright law (e.g., different to trade mark law, copyright protection cannot be renewed), but it also considers re-appropriation of cultural expression as aggressive techniques of artificially prolonging IP protection – something, Justice Scalia at US Supreme Court has labelled as “mutant copyright” in Dastar v. Twentieth Century Fox in 2003.

In the EU, the public policy/morality ground has been traditionally relied on to object to obscene expression. The focus has been on the whether the sign offends, thus tying morality to public policy (See also another Grand Board decision on public policy and morality: 30/01/2019, R958/2017-G, ‘BREXIT’). A notable example is the attempt to register the ‘Mona Lisa’ painting as a trade mark in Germany. The sign was eventually not registered, but not due to clash with public policy and potential artificial extension of copyright through the backdoor of trade marks, but because the sign lacked distinctiveness. Consequently, the EU understands the public policy and morality ground in a rather narrow and limited manner, namely linked only to offensive use.

Overlap of IPRs happens all the time: a patent turns into a copyright claim (C-310/17 – Levola Hengelo and C-833/18 – Brompton Bicycle), whereas design and copyright may be able to co-habit in the same item (C-683/17 – Cofemel). All would agree that an unequivocal law prohibiting overlaps of IPRs is not desirable from a policy perspective. Yet, you may feel somehow cheated when your favourite novel is finally in the public domain due to copyright expiring (which, by the way, already lasts the life of the author plus seventy years), but protection has been “revived” through a trade mark. Trade marks initially last for 10 years, but they can be renewed and thus protection lasts potentially forever (what a revival!). Therefore, there may be some very strong policy reasons against this specific type of IP overlap and extension of IPRs. Like the European Copyright Society has said in relation to Vigeland, “the registration of signs of cultural significance for products or services that are directly related to the cultural domain may seriously impede the free use of works which ought to be in the public domain. For example, the registration of the title of a book for the class of products including books, theatre plays and films, would render meaningless the freedom to use public domain works in new forms of exploitation”. To that end, Martin Senftleben’s new book turns to this tragic clash between culture and commerce. He vocally criticises the “corrosive effect of indefinitely renewable trademark rights” with regard to cultural creativity.

As for ‘Animal farm’ and ‘1984’, the EUIPO’s first instance did not go down the public policy grounds road. This is unfortunate as lack of distinctiveness for well-known titles such as ‘Animal Farm’ and ‘1984’ is difficult to articulate as the Board of Appeal itself underlines – the Office’s guidelines are confusing (some titles have been protected and others not). Besides, lack of inherent distinctiveness can be saved by virtue of acquired distinctiveness (something the Estate of the Late Sonia Brownell Orwell has explicitly mentioned they will be able to prove, should they need to). Considering that the rightholder here would be the Estate of the Orwell family, proving acquired distinctiveness of the titles for the requested goods and services would not be particularly difficult. On that note, a rejection on the ground of public policy/morality can never be remedied through acquired distinctiveness. Thus, it would perhaps have been more suitable to rely on public policy and establish that artificially extending the IP life of these cultural works is not desirable.

Well, the jury is out. One thing is for sure – the discussion at the Grand Board will be heated.

Alina Trapova

Svenskt Tenn, as trademark and copyright holder over a renowned design pattern of a furnishing fabric, filed a lawsuit against Textilis, a UK company that sells textiles in the UK, arguing infringement of its rights and asking for an injunction prohibiting such sales.

Svenskt Tenn, as trademark and copyright holder over a renowned design pattern of a furnishing fabric, filed a lawsuit against Textilis, a UK company that sells textiles in the UK, arguing infringement of its rights and asking for an injunction prohibiting such sales.

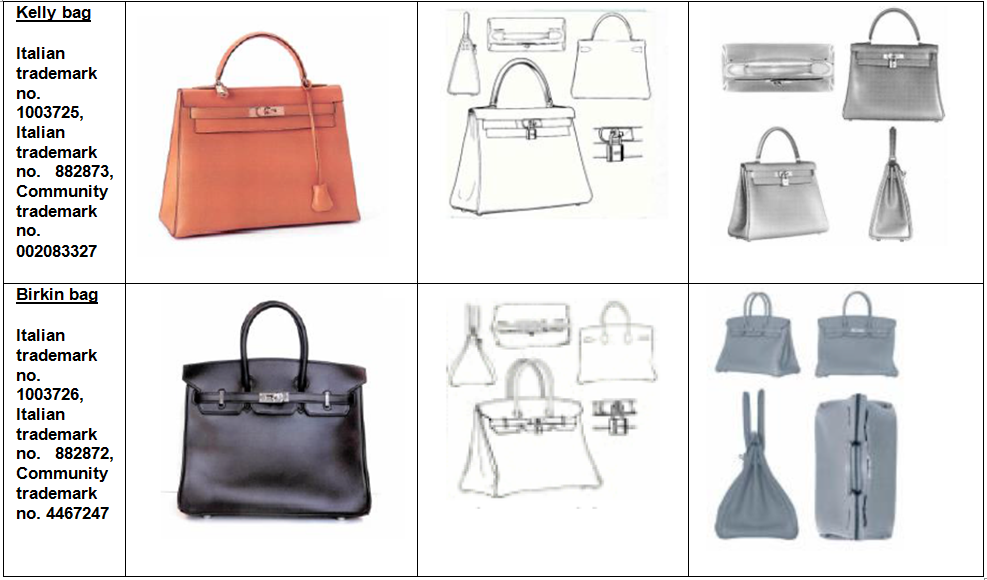

(filing number

(filing number  (filing number

(filing number  (filing number

(filing number