On 23 March, the Italian Competition Authority (ICA) published a 105 pages report providing the Italian Government with a number of pro-competitive reform proposals in view of the forthcoming annual Competition Act (full report in Italian here). This last can be read as the outcome of a constructive dialogue between the ICA and the Government, whereby the first clarifies how to unlock the Italian market competitiveness and the latter may turn these suggestions into binding law. It falls outside the scope of this summary to examine whether, since the entry into force of the Competition Act in 2009, the Government year by year in charge followed the advices of the ICA. In any event, the recent call of Prime Minister Draghi himself for the ICA opinion during the opening speech at the Italian Parliament, bodes well for an effective 2021 Competition Act.

Covering a wide range of topics, the report overall implies the ICA embraced the new EU wide zeitgeist of the coming years, namely, sustainability and digitalization.

The reform proposals focusing on the connection between competition law and sustainable development, indeed, echo and tailor to the Italian markets’ peculiarities the innovative studies released by the Dutch and Greek Competition Authorities (and the recent report of the CMA). As for the digital sector, two proposals for legislative amendments concerning, first of all, the economic dependence law and, secondly, an ex-ante regulatory framework for digital platforms, stand out for the radical impact on the ICA enforcement regime they could have.

With regard to the first point, the Italian Law 192/1998 (“Law on Subcontracting in Production Activities”) imposes companies with a strong bargaining power against customers and/or other companies to avoid any abuse of this situation and related economic dependence on the latter. The economic dependence is determined according to the following criteria:

- the possibility for the company to impose an “excessive imbalance of rights and obligations in the companies’ commercial relationships”, and

- the “effective possibility”for the alleged abused company in“finding satisfactory alternatives on the market.”

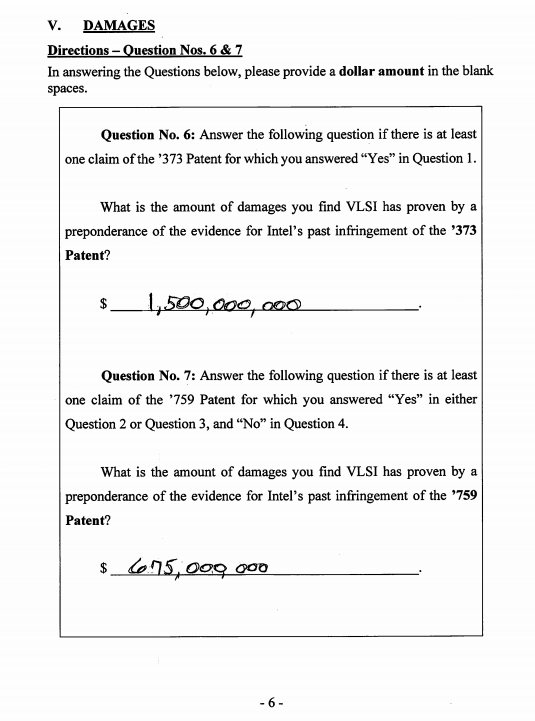

The available remedies against this abuse consist in declaration of nullity of the agreement concerned, injunctions and compensation for damages. Remarkably, within this assessment, it finds no room neither the (costly and time consuming) antitrust analysis of firms’ dominance in a given market nor the assessment of anticompetitive effects herein occurred. Conversely, it shares with the abuse of dominance legal institute the up to 10% fines of the turnover of the company concerned the ICA may impose and the penalty payments in case of non-compliance with the ICA’s decision.

Against this background, an emerging trend pioneered by new legislation adopted in Germany and Belgium and by a more aggressive enforcement by the France antitrust watchdog, is revitalizing the legal instrument at hand, sharpening its teeth.

The ICA is following this trend setting its sight on digital platforms. The core of the proposal rests upon the introduction of a rebuttable presumption of economic dependence “in case a company make use of the intermediary services provided by a digital platform holding (…), a crucial role in reaching end users and suppliers” (also due to network effects and/or data availability it can leverage ). A list of non-exclusive forbidden conducts supplements this proposal, fattening this newly shaped notion of abuse of economic dependence and enhancing the legal certainty for digital platforms. These are:

- “directly or indirectly imposing unfair purchase or selling prices, other unfair conditions or retroactive non-contractual obligations;

- applying dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions;

- refusing products or services’ interoperability or data portability, thereby harming competition;

- subordinating the conclusion and execution of contracts and/or the continuity and regularity of the resultingcommercial relations to the acceptance by other parties of supplementary obligations which, by their very nature and according to commercial usage, have no connection with the subject of such contracts;

- providing insufficient information or data on the scope or quality of the service provided;

- unduly benefitting from unilateral obligations that are not justified by the nature or the scope of the activity provided; in particular, by making the quality of the service provided conditional upon data transfer in an unnecessary or disproportionate amount”.

In sum, by overturning the economic dependence burden of proof on the platforms’ shoulders, if approved, this ambitious reform proposal will lead the enforcement toolkit under exam towards applications never tested before, opening a new chapter of the intriguing debate on the intertangles balance between “purely antitrust based” enforcement instruments and contract law grounded ones.

The second proposal sees the ICA willing to be armed with an ex-ante regulatory tool for digital platforms modelled on the recently implemented German one. Clarifying why an antitrust authority asks to be equipped such powers would need an ad hoc article (and probably a more competent author). Yet, for those brave enough desiring to learn more about the challenges competition law is facing in dealing with digital platforms, these reports are a good first step:

- EU Commission, “Competition Policy for the digital Era”

- Italian Competition Authority, Authority for the communications Guarantees, Authority for the protection of personal data, “Joint sector inquiry” (in Italian)

- Digital Competition Expert Panel, “Unlocking digital competition”

- University of Chicago, Stigler Center, “Stigler Committee on Digital Platforms: Final Report”

Herein it is merely underlined how it is widely accepted among antitrust scholars and practitioners the traditional ex-post antitrust enforcement rules are keeping pace with the challenges posed by global digital players. The abovementioned Commission report notably stressed the digitalization of the economy requires “a vigorous competition policy regime” that, nevertheless, “will require a rethinking of the tool of analysis and enforcement”. This rethinking is currently leading within the EU towards the development of a synergy between antitrust enforcement and regulatory legal instruments (this should not surprise, having Europe a long tradition of combining competition law and regulation in order to achieve similar policy objectives – e.g. the regulation of international roaming charges, Interchange Fee Regulation for the financial industry). The EU Commission draft Digital Market Act, being the last and most debated example of this policy choice, aims at monitoring certain anticompetitive behaviors carried out by the so-called Gatekeepers, those market actors that control the entry of new players into the digital market.

National Competition Authorities are pursuing the same path. In January 2021, the German Parliament adopted an amendment of the German Antitrust Act, introducing, among other things, a new weapon for the Bundeskartellamt to act against platforms and assess network effects. The reform proposal of the ICA mirrors this amendment.

This last introduces the legal notion of undertakings having “primary importance for competition in multiple markets“ (i.e. the Gatekeepers). The ICA shall declare this peculiar legal status following this non-exhaustive list of criteria:

- “the dominant position in one or more markets;

- the vertical integration and/or presence on otherwise related markets;

- the access to data relevant to competition;

- the importance of the activities for third parties’ access to supply and sales markets and the

- related influence on third parties’ business activities.”

Once approved the status of Gatekeeper, in addition to the general rules governing abuse of a dominant position contained in 3 of the Law n. 287/90, the undertaking concerned is subject – for five years since the ICA declaration – to seven black-listed conducts:

- “giving preferential treatment, in the supply and sales markets, to its own goods or services against other companies’ ones, in particular by giving preference to its own offers in the presentation or by pre-installing its own offers on devices or to integrate them in any other way into the companies’ offers;

- taking measures that hinder other companies in their business activities on procurement or sales markets, if the undertaking’s activities are important for access to these markets;

- hindering other companies on a market on which the undertaking can rapidly expand its position, even without being dominant, in particular through tying or bundling strategies;

- processing competitively sensitive data collected by the undertaking, to create or appreciably raise barriers to market entry;

- impeding the interoperability of products or services or the portability of data;

- providing other companies with insufficient information about the services provided or otherwise make it difficult for them to assess the value of this service;

- demanding advantages for the treatment of another company’s offers which are disproportionate to the reason for the demand, in particular by demanding for their presentation the transfer of data or rights which are not absolutely necessary for this purpose.”

The aforementioned prohibitions do not apply to the extent that the Gatekeeper demonstrates that its conduct is objectively justified. It is not yet clear whether this burden on companies is to be understood in the same way as the traditional discipline on abuse or whether in addition to reasons of efficiency, public interest reasons (e.g. safety) could also be included. In case of non-compliance, the ICA could fine the undertakings concerned and/or impose behavioral or structural remedies to put an end to the infringement and its effects or to prevent a repeat of the conduct.

In conclusion, while the above reported reports made the last years a period of reflection for competition law, the antitrust watchdogs are now making their moves to tackle a number of shortcomings the rise of platforms led to. Despite sharing a basic premise – the perceived inherent limits of ex-post antitrust enforcement – as far as it can be assessed at this preliminary stage, the regulatory models under discussion give rise to several questions.

It is still unclear, indeed, how the concurrent application of antitrust and regulatory powers (both at EU and national level) will work when a conduct simultaneously violates competition law and harms market contestability or P2B fairness. On the same vein, how the synergies between antitrust and regulatory powers can be maximized without harming legal certainty and predictability (without forgetting procedural safeguards, above all, the ne bis in idem principle)?

One could further pinpoint an apparent lack of awareness of the intersection between competition and other regulatory protections – such as, for instance, privacy – in the digital sector, and thus the need for forms of coordination and shared responsibility among all authorities with functions in the digital sector. Indeed, some of the above reported obligations on Gatekeeper, such as those relating to interoperability and data portability and to the prohibition to introduce or reinforce entry barriers based on data exploitation, could give rise to tensions with the legislation – and the Authority empowered to surveil – on the processing of personal data. In this sense, the absence of institutional cooperation let foresee a bumping road ahead for the governance of the digital economy. Yet, by providing for, as an example, rules on information exchanges between authorities or even co-responsibility between authorities in some areas, the Italian legislator could still anticipate these overlaps (not least giving the impression that taking the best from other countries should not set critical thinking aside).

Andrea Aguggia