Piaggio, the Italian company producer of the world wide famous Vespa scooter, was recently sued by the Chinese company Zhejiang Zhongneng Industry Group (“ZZIG”) in a quite complex case.

ZZIG offered for sale three scooters named “Revival”, protected by a Community design registration no. 001783655-0002, “Cityzen” and “Ves”, the shape of which was not covered by any registered IP right in Italy or in the European Union.

As to Piaggio, the company owns the Italian 3D trademark no.1556520 claiming priority of the Community trademark no. 011686482, filed on 7 August 2013 and registered on 29 August 2013.

When Piaggio obtained the seizure of the three above motorbike models in the context of a Fair held in Milan, the Chinese company started an ordinary proceeding on the merits before the Court of Turin against Piaggio, seeking the declaration of non-infringement of Piaggio Vespa 3D trademark by its “Revival”, “Cityzen” and “Ves” scooters. Besides, it asked a declaration of invalidity of Piaggio’s Vespa trademark, based on the fact that it was anticipated by their design and thus not novel. Also, it held that the 3D trademark was void, as it does not respect the absolute ground for refusal established by the law.

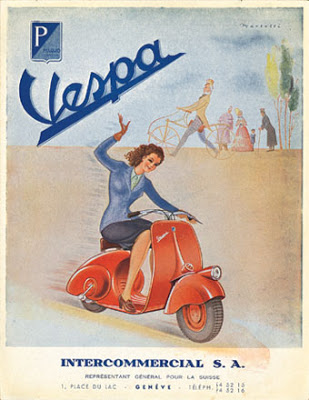

Piaggio resisted and asked the Court of Turin to reject the above claims, declare that the Vespa shape is protected under copyright law, trademark law and unfair competition law and that those rights were infringed by ZIGG three models of scooters. As a matter of fact, Vespa was offered for sale by Piaggio since 1945.

First of all, the Court of Turin declared that the Vespa trademark does not lack of novelty, as it reflects a model of Vespa marketed since 2005, before the commercialization of ZZIG first scooter, i.e. “Cityzen”. Moreover, the Court of Turin excluded the existence of any absolute ground for refusal, stating that its shape was not technical nor standard and not even substantial as the reason why consumers chose the Vespa were not merely aesthetical. Based on these findings, the Court finally affirmed that only the “Ves” scooter constitute an infringement of Piaggio trademark.

This said, the Court of Turin further held that the Vespa shape is eligible for protection under copyright law, as it is since long time worldwide recognized as an icon of Italian design and style, shown in advertising and movies, presented plenty of times at museum and exhibitions and part of many books, articles, magazines and publications. All considered, safe and sound evidence show that the shape of Vespa is unequivocally believed to be an artistic piece of designs by the main communities of experts worldwide. Nevertheless, the Court held that, again, only Ves scooter infringed Piaggio rights vested on its scooter as it presents features similar to the ones protected both under the Vespa trademark and copyright.

The decision (full text here) is indeed interesting as it critically examines the similarities and differences between the “original” good and the ones that are claimed to be infringing products and, while asserting the eligibility for protection of the Vespa shape both under trademark and copyright law, it excludes infringement for two products through a detailed and careful examination. This narrow approach is indeed interesting because it affirms the principle that the infringement of designs protected under copyright law shall be evaluated with an analytical examination similar to those applied in cases of trademark infringement.

A doubt might remain about the overlapping of trademark and copyright protection. Since the former never expires as long as the product is on the market (plus the subsequent five years, according to Italian law), one might ask what advantage for the right holder might subsist by ‘adding’ a protection limited in time, such as copyright’s. The answer might be: the dual protection functions as a ‘parachute’ for the case that one of the two, in a subsequent Judgement (Appeal or High Court: Cassazione in Italy) should be successfully challenged by a competitor.

Maria Luigia Franceschelli

Court of Turin, case No. 13811/2014, 6 April 2017, Zhejiang Zhongneng Industry Group, Taizhou Zhongneng Import And Export Co. vs Piaggio & c. S.p.a..